Interactive Cinematic Design, Pt 2: The Ladder

Note: This is Part 2 of a two-part series on interactive cinematic design for The Expanse: A Telltale Series. Part 1 covers the initial Point Targeting System (PTS) prototype—a mechanic designed to give players agency during cinematic sequences. This case study focuses on how that system was adapted and validated through a pivotal narrative moment.

TL;DR

Challenge: Prove the Point Targeting System (PTS)—an interactive cinematic framework—could create engaging non-combat gameplay, not just action sequences.

Solution: Championed and prototyped a high-stakes ladder climb using the PTS system, navigating technical constraints and scope concerns.

Impact: Became the proof-of-concept that validated PTS for narrative-driven gameplay, directly influencing heavy PTS usage in later episodes.

Overview

Shortly after prototyping the Point Targeting System (PTS)—an interactive cinematic framework for player agency—an opportunity emerged to prove the system's real value—not in combat scenarios, but in a high-tension narrative moment. The script for The Expanse: A Telltale Series Episode 1 included a brief sequence where Drummer, the player character, is nearly blasted off the ship's exterior, grabs a ladder in the nick of time, and must climb back to safety. What existed on paper as three to four lines of script became the testing ground for whether PTS could deliver meaningful player agency in emotionally charged, non-combat situations.

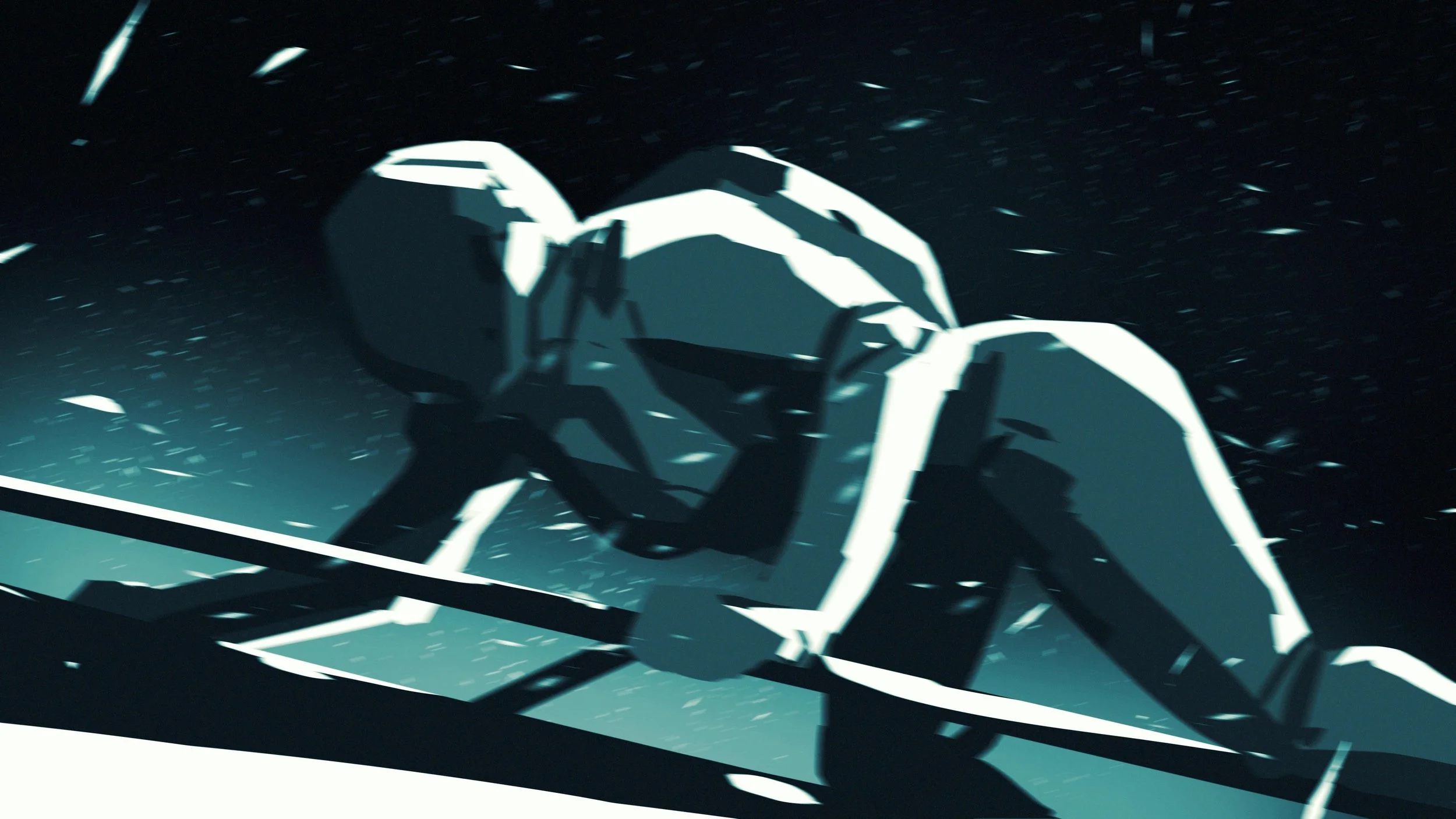

Image from our storyboards providing previs to "The Ladder" moment.

Situation

The PTS prototype had successfully demonstrated technical feasibility but received mixed reception due to its genre mismatch with the game's narrative tone. The team needed proof that the system could work for something other than shoot-outs—a moment that felt naturally integrated into the story rather than borrowed from an arcade game.

Early storyboards for the ladder moment depicted objects flying past Drummer as she climbs. The Game Director created a timed animatic with background music and voice-over, adding visual elements that suggested player input opportunities. While the PTS strike team had concluded, the animation team had bandwidth due to pipeline issues between motion capture and cinematic teams, creating a window to explore whether this moment could become interactive gameplay.

Screen grab of the script displaying the 3-4 lines describing "The Ladder" moment.

Task

The core challenge was transforming a brief scripted beat into a compelling gameplay moment that would:

Validate PTS for narrative tension rather than combat

Demonstrate player agency without breaking cinematic flow

Stay within reasonable scope constraints (the feature was still unproven in full production)

Solve technical challenges inherent to the scene's unusual spatial orientation

The moment had been assigned as standard cinematic work—cleaning motion capture recordings for a straightforward sequence. The decision to make it a PTS gameplay moment was design-driven, requiring buy-in from leadership while keeping scope realistic.

Animatic of “The Ladder” moment from The Expanse: A Telltale Series Episode 1

Action

Championing the Opportunity

After reviewing the storyboard animatic and beginning work on the motion capture cleanup, it became clear this was an ideal candidate for demonstrating PTS in a non-combat context. Reaching out to the Design Lead, the pitch was straightforward: use the available animation bandwidth to block out the moment as a PTS sequence, creating a functional prototype that could serve as a pitch to leadership. The response was enthusiastic but cautious—the feature was unproven in full production, and budget considerations remained uncertain.

The approach: work fast, get it functional in-engine, polish later. The goal was to create something concrete enough to make the case for why this moment deserved to be interactive.

Technical Problem-Solving

Building the sequence immediately surfaced technical challenges that needed creative solutions:

Motion Capture Stitching: The ladder the actor had climbed during the mocap shoot was only six feet tall, meaning each recorded file contained just one step per foot. To create a convincing climb, multiple mocap shots needed to be stitched together—first to establish a base climbing loop, then to add variation through different dodge animations. This foundational work took longer than anticipated but was essential to selling the character's movement.

Spatial Orientation Challenge: The ladder existed in an unusual orientation within the game's world space. In the ship's design, the ladder ran from bow to stern (forward to aft), lying on its side with rungs facing outward on the port side. For animation work, this meant operating in unconventional axes with high risk of gimbal lock (rotation control issues). The solution involved repositioning the ship geometry in Maya so the ladder sat near the software's origin point, then establishing a precise anchor point in the level to maintain the animation's spatial relationship to the ship.

Camera Constraints: Once the animation was imported into Unreal, a new issue emerged. The in-house cinematic tool, Storyteller, locked cameras to world-space rotation order. With the ladder rotated and positioned at an angle relative to world coordinates, framing shots around the climbing action became extremely difficult. Rough camera work was possible through manual adjustments, but it became clear the project would need new camera tools to handle scenes in non-standard orientations—a common requirement for a game set in zero-gravity environments aboard derelict ships.

Early blocking of “The Ladder” moment with UI previz mockup and time manipulation.

Designing the Flow

With the technical foundation in place, attention shifted to defining the player experience. Several design questions needed resolution:

Player Control vs. PTS Overlay: Significant discussion centered on whether players should directly control the climbing locomotion. From a gameplay perspective, this was desirable. However, the PTS system functioned as an overlay for player input on top of playing cinematics—not as a locomotion controller. If the player executed an input within the reaction window, the cinematic continued. If they failed, the sequence ended and transitioned to a "fail" state. Building true climbing control would have required new locomotion systems, putting it outside scope for design, tech, and animation teams.

Sequence Structure: The final flow established clear PTS interaction points:

Drummer grabs the ladder with one hand and nearly swings off—player has a PTS input to grab with the second hand

Drummer begins climbing; debris flies toward her requiring dodge inputs

The dodge sequence: right, left, right, right, left

This structure shipped in the final game. Earlier iterations included additional complexity—Drummer climbing the full ladder length with a dramatic flip where she nearly gets knocked off, requiring the player to re-grab the ladder. This version was simplified due to scope concerns and the feature's unproven status.

Branching Considerations: Early mockups envisioned presenting the player with two dodge options—left or right. Selecting correctly would continue the cinematic; choosing incorrectly would trigger a fail sequence showing Drummer hit by debris. While this would have utilized the PTS system's full branching potential, it quickly became clear that this level of cinematic variation was cost-prohibitive. The moment existed as three to four lines in the script, scoped as a standard cinematic. Adding full branching would have significantly increased mocap, cinematic, and animation costs beyond what the design-driven initiative could justify.

Early iteration of “The Ladder” moment displaying the sequence structure and PTS action set list.

Implementation and Iteration

Getting the sequence functional in-engine involved layering multiple systems:

Animated "falling" debris objects (initially using placeholder pink drawer geometry) timed to match the climbing animation's pacing

PTS target markers attached to debris, communicating with the UI to display countdown timers

Time dilation triggered by timeline markers, slowing the sequence during player input windows and allowing designers to adjust dilation intensity and timer duration

Fail state sequences that were generic enough to be reused at any point along the ladder climb

Camera work progressed through multiple phases. The initial pass established framing sufficient to sell the moment and identify the technical feature request for proper camera controls. Later in development, the cinematic team polished camera positioning and framing, ensuring players could consistently see incoming debris and that UI elements aligned with the animation's timing and vision.

Results

Tangible Outcomes

Validated System for Narrative Gameplay: The Ladder became the definitive proof that PTS could create compelling player agency in non-combat, story-driven moments. Where the prototype proved technical feasibility, The Ladder proved design value.

Production Template: The workflow, technical solutions, and scope considerations established during The Ladder's development directly informed subsequent PTS moments throughout the series. Episode 5 featured heavy PTS usage, with the majority of its 40-minute runtime dedicated to interactive sequences.

Technical Infrastructure Identified: The camera orientation challenges discovered during development highlighted critical tool needs for the full project. Many scenes were planned in unusual spatial orientations due to the zero-gravity setting, making proper camera controls essential beyond just PTS moments.

Cross-Discipline Prototyping Value: Demonstrated that animator-driven design work could accelerate feature validation when teams had bandwidth and the right opportunities emerged.

Key Lessons Learned

Scope Metrics Break Down

The project used "cinematic minutes" (CM) as the primary scoping metric. Each script line received a rough CM estimate, which teams used to calculate workload and resource allocation. This system worked well for standard cinematics but broke down entirely for PTS moments.

The Ladder existed as three to four lines in the script but required substantially more work than those lines suggested—motion capture stitching, interactive design, multiple animation states, fail sequences, and technical problem-solving. The disconnect between script representation and actual production cost became a critical lesson: interactive moments need explicit representation in scripts and scoping conversations to ensure downstream teams understand what they're building. This finding influenced how future PTS moments were documented and planned.

System Constraints Shape Design

The PTS framework's architecture as a cinematic overlay system—rather than a player control system—fundamentally shaped what types of interactions were possible. The desire to let players control climbing directly was understandable from a gameplay perspective, but the technical reality required working within the system's designed capabilities. Understanding and embracing these constraints early prevented scope creep while still delivering meaningful interactivity.

Technical Discovery Serves the Whole Project

Problems that surfaced during The Ladder's development—particularly camera tooling needs—had implications far beyond this single moment. Identifying these requirements early in production allowed the team to prioritize tool development that would benefit numerous scenes across the game, not just PTS sequences.

Conclusion

The Ladder transformed from a brief scripted moment into the proving ground for PTS as a narrative design tool. Where the initial prototype answered "Can we build this system?", The Ladder answered "Should we use it?"—and the answer was a resounding yes. The sequence demonstrated that meaningful player agency could exist within cinematic storytelling without sacrificing emotional impact or narrative flow. This validation directly influenced the series' creative direction, with later episodes leaning heavily into interactive moments that kept players engaged during high-stakes sequences. The lessons learned about scope, technical infrastructure, and cross-discipline collaboration shaped not just how PTS moments were developed, but how the team approached interactive storytelling in production.